Disability And Academia: A Strange Pair?

Disability is often a non-topic in academia. How can the scientific community unlock the potential of lived experiences of students and staff with disabilities? PhD researchers Anaïs van Ertvelde and Andries Hiskes get into a conversation about experiential knowledge, representation and access.

Experiential knowledge is a hot topic. Whenever we speak of a minoritised group, people call for the involvement of people who have direct experience with the subject. How do you see this idea reflected in academia and what are your experiences with it?

Andries: Disability is a socially and politically engaged topic at the moment, especially in the Humanities. As a scholar with a disability researching disability in literature and art, I’m often asked how my own disability plays a role in my research. Of course I’m held accountable for my work, but at the same time my research is not about me. I want my work to be judged by its quality.

Anaïs: Researching disability as a researcher with a disability automatically puts you in a non-neutral position. Somehow, people assume that there is a connection between Disability Studies and a person’s own disability. I think disability is an incredibly interesting analytical category for all scientific disciplines. Why am I asked whether my research into disability history is a therapeutic project, but a female scholar researching 1970s feminism isn’t?

Andries: The issue of “objectivity” is often raised when experiential knowledge is involved. Literary Studies is concerned with interpretation, objectivity in my discipline consists of applying methodologies correctly. I’m interested in specific cultural contexts, not necessarily objectivity – whatever that may mean. At the same time, most disability-related topics become political at some point. This might not be obvious in medicine or the natural sciences, but think for example of NIPT (Non-Invasive Prenatal Test) tests to check foetuses for Down syndrome. The rapid normalization of such a test and its potential impact happens with only limited discussion at the societal level.

Anaïs: One very peculiar thing I notice is that I’m often perceived as an authority because of my disability. The flip side is that I’m sometimes seen as a research subject. These are complicated experiences to navigate; the only time I actually perceive a level playing field is when I’m amongst other scholars with disabilities.

How are researchers with disabilities represented within academia? Why do researchers with disabilities hardly move up in universities and what can we do to change that?

Anaïs: Oftentimes, the researchers with disabilities who reach higher positions are the ones I call “abled disabled” [ref. Tanya Titchkosky]. Their access needs are not too complicated for academia and often they don’t have many intersecting marginalised identities. It gets more complicated when someone’s access needs require structural adjustments to universities’ infrastructures. The financial aspect is an important factor, but also the lack of role models and inaccessible architecture.

Andries: Once I attended a PhD defence, where the PhD candidate had to step onto a raised platform. When I mentioned that this would be inaccessible to some people, the response was: “We’ll fix it when the first wheelchair user comes for their PhD defence.” That’s a shame, because it can discourage people from pursuing their ambitions. You can’t become what you can’t imagine yourself to become. When disability is involved, academia often has implicit assumptions about a person’s physical and mental capacities and productivity.

Anaïs: I agree, academic careers are tailored towards non-disabled bodies and minds. Think for example of the long working days (including nights and weekends), deadline-driven projects and never-ending conference visits abroad. Are we actually willing to rethink and change that?

Andries: It’s often up to students and staff with disabilities to raise issues like inaccessibility and accommodations. The reactions are often quite dramatic, emotional and apologetic. Accommodating these reactions is usually up to the person with the disability, which is taxing. Accessibility is a mindset you can practice, hypersensitivity and guilt are not helpful. I’d rather want to see concrete actions and a feeling of shared responsibility for developing new ways of interaction.

How can academia lead the way to a more accessible and inclusive society? What does academia look like in an ideal world?

Andries: Universities are part of society, so change in one leads to change in the other. One step we can take is rethinking the language around disability. “Special needs” is a term that’s often used, but it’s actually stigmatising for students and staff with disabilities because it reaffirms the nondisabled norm. If we can go beyond the usual arguments of “it’s only small numbers of people” and “accommodations must be reasonable”, we can work towards a more accessible university for all.

Anaïs: It’s important to involve students and staff with disabilities every step of the way. They know themselves best! It is the responsibility of people with and without disabilities alike to learn about disability, so that we can work from a common ground. Disability relates to all of us, the struggle with the limitations of our bodies and minds is universal. Taking a disability perspective is crucial in addressing issues such as burnout and work pressure. There is so much to learn from the insights of students and staff with disabilities.

Do you want to know more about disability and academia?

- The Access & Support Platform is a network by and for students and staff with disabilities at Leiden University.

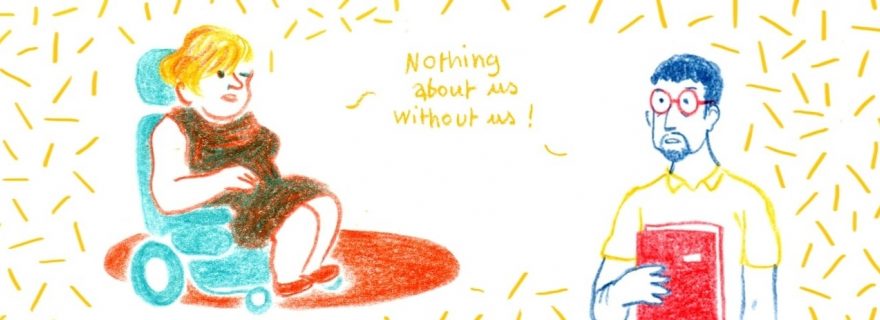

- Comic for the ERC-funded project Rethinking Disability: the Global Impact of the International Year of Disabled Persons (1981) in Historical Perspective.

- Vlog: LUCAS Explains #8: Stop Staring. How can we change the way disabled bodies fit into the world by changing how we look at them?

- Annual Disability Lecture at the University of Oxford 2019 by The Triple Cripples.

- The book “Academic Ableism: Disability and Higher Education” by Jay Timothy Dolmage.

Anaïs van Ertvelde is doing PhD research at the Institute for History, as part of the ERC-funded project Rethinking Disability. Her work focuses on the history of disability movements on various national levels and on an international level. Anaïs is also a writer, journalist and podcaster.

Andries Hiskes is doing NWO-funded PhD research at the Leiden University Centre for Arts in Society. His work focuses on affective responses to deviant bodies in literature and art. Andries is also a lecturer at the department of Nursing at The Hague University of Applied Sciences.

0 Comments